John Court Man-in-progress

The text was written by

Paz Ponce Pérez-Bustamante

With an artist

John Court

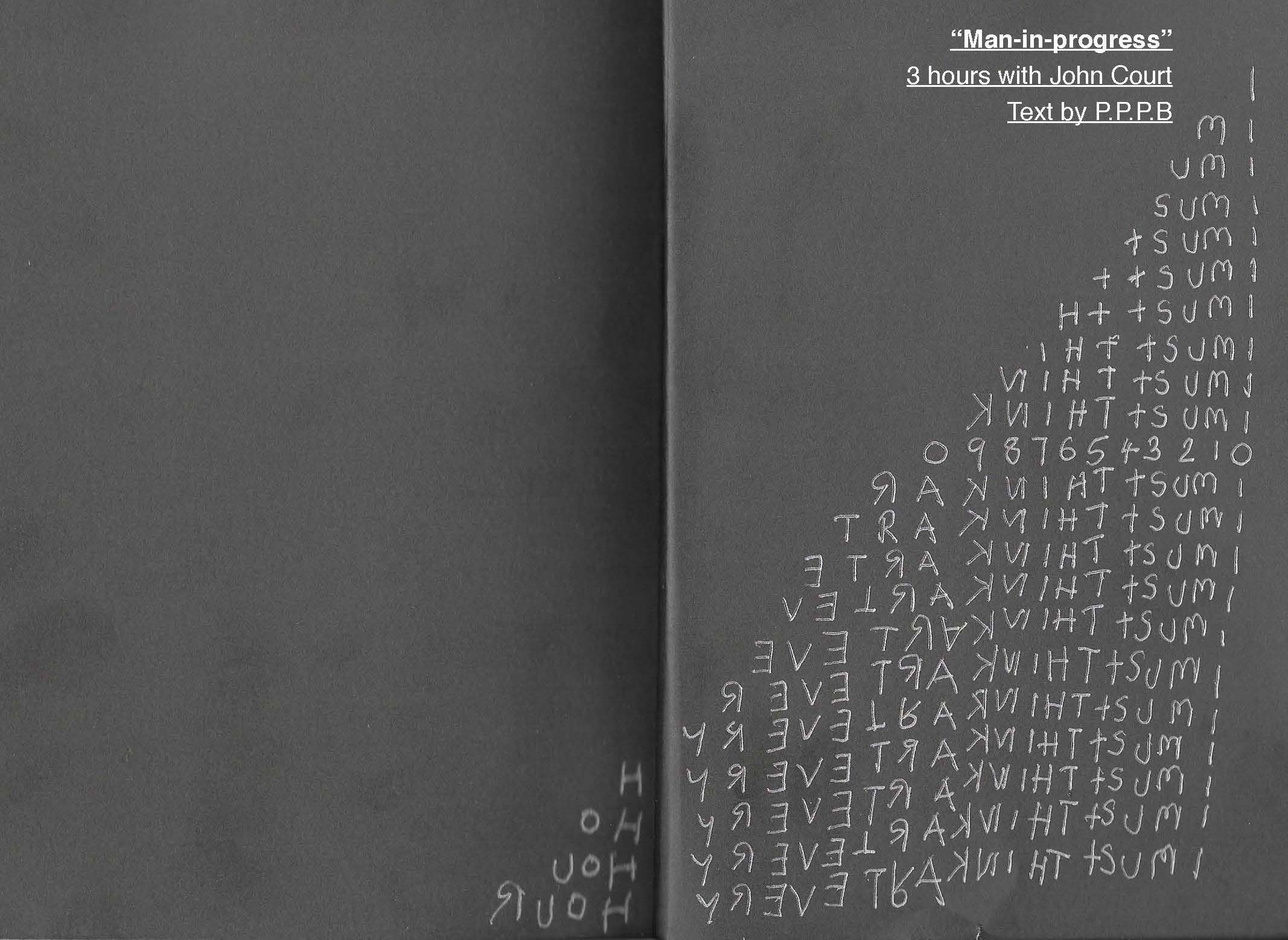

I met artist John Court at a Berliner Café in late November 2017, while his artist in residence program. He gave me his book: “AN IDEA OF PERFORMANCE A IDEA OF ART”. He had written a dedication in the last spread of its 230 pages with a silver pen. The inscription said:

I MUST THINK ART EVERY HOUR.

Over the next 3 hours, he went on talking (and kept on thinking) about art, reasoning carefully about the philosophical core of his durational performances, tracing intentions, sources of inspiration and describing the “creative climate” surrounding each piece. I recorded 2 hours of this conversation, didn’t take notes and not very often did I interrupt him while he was speaking. Court is an incredibly eloquent man who finds no obstacles organizing his thoughts orally. Ironically, the same cannot be said about his way around written expression, a medium resisting him due to an unattended difficulty with language at an early age.

John was born in northern England in 1969 and moved to Finland at the age of 28. An English native speaker living in the (other) north, south of Lapland, he thinks of himself as a foreigner in every language but in art: for him a time-based territory where he is able to articulate full grammatical structures combining a chair, a stick, white chalk, black tape, a ramp, a table with three legs, a brick, his forehead, a few stones, paper and an imaginary ladder. The way these syntactic units are ordered within the phrase, do not alter its basic meaning: time. Time appears as the subject, the object, the verb and all its accompanying circumstances, qualities, complements and pre-conditions for his actions.

— “Time is the biggest thing we have” – he began saying.

— “Many things happen because of time. So many things which have not my control in the performances. When mistakes happen. I only trust time, it gives perspective”.

For a person who-thinks-about-art-every-hour, continuity and progression are very important, energy and engagement are likewise vital to this process. He spent “one year just thinking of being open to the possibility of change” – he said.

— Change within your work? Or change coming from you?

— “Everything, everything, everything in my life. You know, Everything, from the washing up to making the work. Being open to the idea. That I really embrace”.

And then this book came around.

— “Is a book of sketches. I have 10 or 15!”

His arms suddenly open up widening the exclamation. He then listed the content of this publication, which consists of:

1. performances he has done / 2. performances he would … may do / 3. performances he will never do – most of them.

— “It’s continuous, there’s no break, I don’t edit the idea, all they have to be about is performance.

These drawings: they are access points for me to get to the idea, and to the moment when I was thinking that. From the mind, from the taste, from contemplating… Some of them come from the space, but most of them come out from contemplation. Just being relaxed, and focusing and thinking”.

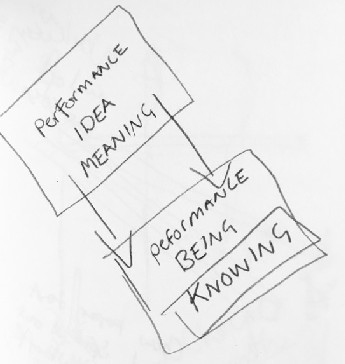

— “I meditate a lot. I think it is a way of thinking, and actually for the duration is great. I meditate the ideas before the shape, or the idea of the object. It really depends. I just float around most of the time, looking for this kind of structure for the idea. I have the idea and then I have the meaning, but then I have the knowing of the work. I think that’s quite important. “Meaning” can be literally spending that time in the space with the object, while I’m making the object, of course, I’m connected with it, becoming friends with my work. The doing and being, I prefer this word; if you put me on a beach I prefer this word: being. Body and mind together. Doing is more brain, is more meaning; while being is more knowing. The idea, when it comes properly in this book; and then meaning — the meaning is a transfer, it can’t be in this part, it can’t be if it’s an object, if it’s me. What I’m trying to understand is what I’m doing. What I’m saying is when I get to knowing, it’s me and the object, all together. There’s no separation. I wanna be in knowing, then I can start exploring my creativity.

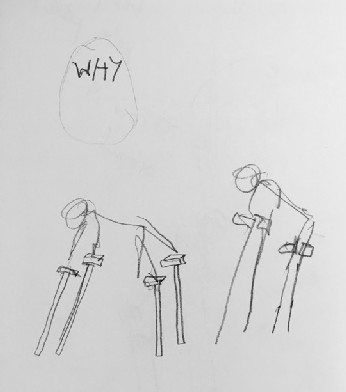

He opened the book from the back, pointing at the last drawing. A double figure of a man on all fours supporting his hands and feet on crutches. The chest slightly raised. Above the image, a word within a circle: WHY.

— That’s why I did these drawings, because I didn’t have the language. And I do have this other language which… if I use a table, and a chair… I make the object like a sentence. Or like the structure of a sentence. Or a word as well. The word is pretty important for me. I just cannot function with them. I love words but when they become sentences it just doesn’t make any meaning.

— Are you frustrated by language?

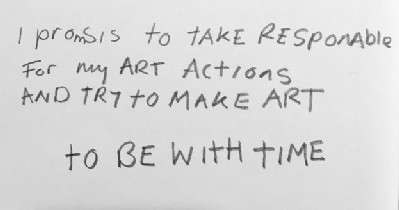

— I suppose basically what I was more frustrated with is people wanting to know what I wrote about my art, than looking at the drawings. So I did this kind of statement. That was the basics of that piece.

— John, can you name those basics?

— Yes, I would say is not a movement, is action. I would say time…

— Do you think in verbs?

— I don’t really know what verb means.

— An action… something that calls for something to happen. Like in move, breath… Or you think more in qualities? like cold, beautiful, strange…

— No. I don’t have that much depth in the language. It just spins unconsciously.

He ran his hand over the drawing and shook the book in the air, as if wanting to clear the confusion, and concluded:

— “The only thing that makes sense for me, is to perform, to be in action. But the basics are not being covered by performance these days. Specially time and duration. I have seen duration, but it never has any time…”

After the hours I spent with John Court, I came to understand his actions like a form of orality, his drawings as a mnemonic technique, and time as the written form of these actions. Both writing and orality are basic communication forms to preserve and deliver knowledge over time. While the two can be understood as works-in-progress, the first allows editing and reformulating of its meaning before made public, whereas the meaning of the latter exists only before a public. As a system, writing frees the mind towards more abstract thought, and is intrinsic to philosophy as a means of thought organization. Orality, on the other hand, has no texts. Knowledge, once acquired, has to be constantly repeated or it would be lost: fixed, heavily rhythmic formulaic thought patterns are essential for wisdom and effective administration. Serious thought is intertwined with memory systems. Mnemonic needs determine even syntax.

8 hours performance

8 in DigitaLive, curator Jonas Stampe at YouYou

Contemporary Art Centre, Guangzhou, China , 2014

Photograph by Jiayi Chen

In the total absence of any writing, there is nothing outside the thinker, no text, to enable he or her to produce the same line of thought again. Aides-mémoir such as notched sticks or a series of carefully arranged objects will not of themselves retrieve a complicated series of assertions. How in fact could lengthy, analytic solution ever be assembled in the first place? An interlocutor is virtually essential: it is hard to talk to yourself for hours on end. Sustained thought in an oral culture is tied to communication. But even with a listener to stimulate and ground your thought, the bits and pieces of your thought cannot be preserved in jotted notes. How could you ever call back to mind what you had so laboriously worked out? The only answer is: Think memorable thoughts.

Walter J.Ong, “Orality and Literacy -The Technologizing of the Word”, 1982, 2002, Routledge. pp. 33-36

Orality should be then understood as a human characteristic, not one belonging to a given culture, time or place. These considerations on writing and orality are interesting when we look at the role which knowledge, rhythm, repetition, memory and the presence of a public play in Court’s performances, as a system to generate more memories and memorable thoughts and explore his identity inside the circularity of time.

Now, the ways in which John Court inscribes himself in the present through his art, vary, and consist of a rich iconography of subtopics through a vocabulary of repetitive gestures he has effectively administrated through the years in his durational performances. This paper is based on a transcription of the conversation, interspersed by images of the works some of his seminal ideas reference to, in a non-linear manner.

He has a concept in mind now, he says, of going backward. He began exploring it in the workshop he came to give in Berlin, “back to basics: … time”, hosted at Grüntaler 9 with members of the Association for Performance Art – Berlin (APAB).

Back to basics: … time – a durational

workshop by John Court at gr_und Gallery, 20.11.17

Organized by Association of Performance Art – Berlin

Produced in the frame of Berlin Sessions Residency.

Images courtesy of APArtBerlin

— I thought I’m gonna give one exercise, about time, and we are going to repeat it. It’s all about repetition. I just tell them carry on. “Not sleep is the main thing, and not to close their eyes” if you close your eyes you can imagine everything and that’s great but that’s not reality, you have to look, you have to be present.

— It was an 8 hour performance duration workshop. How do you arrive at this perfect time sculptures in terms of duration?

— For me, I just want to empty myself. If I am doing a single action, I just do one action, and when I can’t do it anymore it stops. But what happens when the action is done but I’m not empty, I’m not finished? And I always have to finish. Because it never finishes, and it never begins. So what I have seen here in Berlin, the performances, same people come, same people are there, same people organize them. I’ve never been able to do that, to be in and out the performance. I can’t transition from being in the performance to being out. I just do from begin to end. Because every moment that there’s action, is really there. So I don’t necessarily think I need to make physical work. I don’t actually think there’s anything left.

— This is why you are interested in working backwards?

— “I just change in completely different times now, it’s something I have never done before. I’m looking for a space in Berlin, to perform next year”.

— What is that you are looking for?

— “Something that doesn’t have a cube. I would like to build a ramp. To climb up the wall. An Indoor space. I also want it to be days. 40 or 48 hours. A week full-time. I haven’t committed myself to that long because I have been working in festivals, they allow you these periods of time, these situations … I’m kind of scared about it. For me performing in a festival or performing in a different culture where you don’t live is much more challenging. And the sense of urgency feels a bit different for me. Berlin stays in Berlin, that’s the problem”.

— What do you mean?

— “I mean that the performance people have been focused on performing in Berlin. Because the spaces are cheaper than in other scenes, and their only need is to express their art anyway, it’s not like they are dying, which is something I think is really interesting. There are lots of performance groups here, and they are incredibly supportive of each other, I think that’s really nice. In performance, it ’s always been very supportive in festivals structures mostly, but here is specially strong. Helsinki is completely different performance-wise. If I would be Finish I would live here, I would only compare it with London perhaps. In Finland you can’t talk to anybody, is different from here. But here you just talk to people.

But here in Berlin is very difficult for me to think. Whereas in Finland….”

— What is the keyword you are looking for? In one word…

— Isolation. I don’t speak finish, I am focused 100 % on my art. Even when I’m sleeping I would consider I’m still thinking about art. When you are in a society or a group, it becomes the same in a way. I’m interested in the ideas of the curators and in how people think, but the art I have seen most of it I don’t trust. I think people want to be here, in Berlin, and they really want to be artists. Not many people want to be an artist in Finland, they just want the lifestyle, but they are not ambitious. Because everybody gets funded when they reach a certain level. And if they change too much they may stop being funded… But people want that. It comes down to trust and responsibility.

— So recognition is actually a problem.

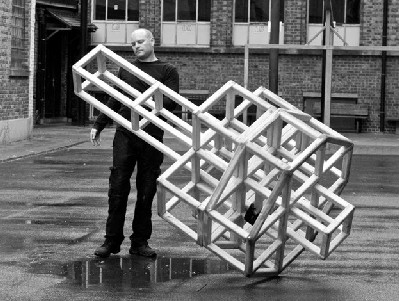

— Well, I think art is more conceptual, more about the idea than the image. Or it should be. I’m more interested in the idea, even though there is aesthetic beforehand, because I think about composition and stuff like that, but you know people say to me “they are looking for the image”, but how can that be? When the only thing I’m interested in is the action. And the action is visual as well. I can actually see the action. Or if I am building a structure, I can spend weeks constructing it in my mind.

But they cannot see the action in the performance, they are looking for an image, and this is not here, people talk about an image and not at the performance. And if you look at the photographs you see nice images but they actually cannot see the images, because they’re doing it. So what do they do before? Do they take a video and see how it looks?

4 hours performance

Untitled in Live Action 9, curator Jonas Stampe at Gothenburg

Konsthall, Sweden. 2014

Photograph by Li Qijian

But that’s not the business I’m in. I can’t see the image in the action. It’s all for the action. And it’s not for the image. Of course, beforehand I’m kind of thinking yes I need to wear black, and white chalk, and then I have the black tape. I use the black tape because actually, I like the feel of it. It has a stickiness which really works well with the shoulders and parts of the body and it’s like an internal object, because of the tape.

— You can’t see the image in the action, you can’t see the meaning in the sentence… and the entire process is about giving birth to this internal object. So it’s a very sculptural way of thinking (this way of talking)…

— If I’m not using objects, If I’m minimizing my objects, is about the action, I can see where the object talks about the action. Maybe I have the idea of doing that, then I have the meaning of doing that, so why I am doing that? Perhaps it happens in my mind and later my body starts speaking, I mean the muscle is thinking. And then I can get back to this bodily memory experiences from the past, which I get all the time. Specially the childhood. When I’m holding around a stick, or carrying around a stick, or holding my mother’s hand. And from there when I went clockwise, I think, actually, when the stick drops, I wanna go anti-clockwise cuz I wanna pull back time, I want my mom back. I’m performing this performance. I don’t care about the performance. I kind of want to feel that loss, and then it becomes very weird, you see all these things happening. I’m trying to project, sometimes the audience can feel it, sometimes the object, most of the time nothing can happen, you just be open to that, you are just trying to use that, so through that repetition I’m able to do that. The muscle memories, which is something I’m working a lot with now, it happens all the time. And I really I just have to decide the meaning and there is where I talk about knowing. Maybe not really logical.

6 hours performance

Untitled in Performing Drawology at The Bonington Gallery

Nottingham UK, 2016. Photograph by humhyphenhum

— So knowing is remembering? (that’s very platonic).

— I have never been in that moment before, I never really go back to the same moment, it’s always different. That was holding the hand, or have a sense of smiling when you are not smiling, with the carrying the boat, it’s like you have a sense of all these people died. You get really unhappy with this kind of situation.

Saying: repetitive drawing-action. Is like the idea that this drawing, the drawing of the 8, I did this drawing of the 8, and then at some point it was christmas. I had this electric train. And I was back at christmas. And there was my uncle. And I had to play it because I was playing it all day. And he always got really annoyed. But I was back there. It’s quite difficult to do it, and it was 6 hours non-stopping, and I get quite involved in doing it. I think why I am doing that? But when I have this experiences, is like the time goes forward and back. Now actually the best thing is that I can go backward in my life, I don’t wanna get forward. Because we all die. So it can go either way. It depends on where I am at the moment.

— Is it independent of an audience looking at it?

— I think that is the big argument or problem that people have in performance. That is participation in art. And I comment quiet strongly, is this not participation? Is there not a social connection? Is more about human condition connection. I’m getting quiet frustrated with that situation, when I think I’m socially connecting.

4.30 hours performance

Pushing Space at Mope 05 festival, Vaasa Art Hall, Vaasa, Finland.

Image courtesy of the artist

— The expectation for interaction…

— I always embrace the audience. How they are feeling, I’m not sure about the word audience, I definitely don’t like the word witness. But there is something about witness I do like. As I understand the audience is quite appreciative to see it. And the possibility of an audience is why I do it.

— How do you see participation yourself?

When I see or watch a performance, not very often can I feel I’m contributing to the work, I just feel I’m mourning, I’m reading a set of instructions or something I’m also trying to do. Which is great, specially when is conceptual or intelligent. Which I’m really excited about… But when I’m looking at duration, what I hope to get with duration is that you are able to express yourself in the work, which is very difficult to do in participation work. You kind of get caught up into this bubble and again I think the participation at work is more like these shorter works, structured, sometimes controlled and it actually doesn’t give you the freedom. I just can’t see, I like to be part of the work, and I don’t think in participation, I just think in social pressure. Some people want to do it, some people do not want to do it. I’m responsible for my own actions and they are. I would prefer to be touched by the art, instead of the social control. I would prefer to take what I want to take. I’m kind of influenced by life, I have my limitations.

— Are this impressions about social control somehow determined by your experience as a student?

— Certainly. I am more interested in the past, my childhood, I couldn’t read English at school when I was 16. I

stayed quiet. It was really confusing. I did not understand what was wrong. It was really affecting my life.

— Do you think growing up needs a written structure?

— I don’t know but I think in life you need to communicate with words. Specially in school, I just didn’t understand why in school I couldn’t read and I was always face-lying, writing the words, I never got tested, and then the frustration got into being taken out of a classroom. I use physical tools to express myself.

Sketch for “Drawing without seeing (Hearing)”.

Grüntaler 9 at Art Bosphorus, Istanbul, Turkey, 2013. curated by Teena Lange.

— Football was great! Fighting was good… I would just fight every day, with anybody. Because I would be so frustrated. And it was really clear, all they had to do was understand my issue.

— Nobody knew you were dyslexic?

— Not only dyslexic, but to explain what was wrong. And then it was really clear, I can see it now. If I go to school now to do a workshop I can see clearly who is frustrated. Of course, I don’t know the reason of their problems, but you can tell someone has an issue. And that they need to be explained what their issue is, or be helped, maybe the parents need to kind of know to understand what there is. Even still with Finland, I see it when I go to school. I do a lot of work in schools. I went to this school in Brussels that have a lot of refugees. Also, the kids that have a lot of problems in other schools come to this school. A very nice school, I had an amazing experience. So I was going to do a week workshop for the students to make an object. What I asked them to do, is if they could make or draw an object of what the language they use looks like. And also how another language, because they don’t speak French, looks like. To draw a shape. And from those kinds of drawings, I designed this object. I really like this object. Based on a circle and a cross. Is an 8 sided hexicon, or shape. An 0 is an x in Finnish, and an x is an x. So it’s negative. So I wanted to use the negative shapes to make it.

4 hour performance Common Ground in SIGNAL festival

Brussels Belgium. 2017 Photograph by Bea Borgers

— This cross: is it what you call negative?

— Yes, so this shape completely changed the movement. I was more interested in the patterns of what they did, I tried to actually represent in the performance. There were lots of spiral drawings, so I kind of spiraled. I would normally not do that. This was very difficult, but the students were watching and they were so involved in the making. I designed the shape and they produced it.

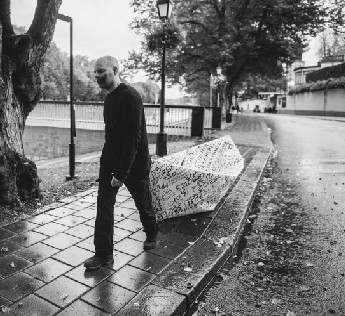

For both performances. In the school yards they have carpentry places. They wanted an object before the festival. So because of the Molenbeek area and the refugee students, I designed a roof. It’s quite questioning a home, or security. Even when I go to a place I feel I don’t have any sense of belonging, you have to hold-on to something. So this is based on this triangle. The title of this is common ground. It’s more about ground than social. You use the same ground. The whole festival was called “common”, which i didn’t know. It was done in urban spaces.

For this object, I also asked them about their language. I asked them to draw the drawings of what they remembered they did when I asked them to draw, and they did it, and I was like “keep doing!” So it became black. It was very nice at some point, these carpentry guys were quiet upset. So I said: “what do you think?” and the guy said: “too much”. And I said: “But when you put more, it means more. Don’t think about the image, think about the content!” I wanted their action.

— So we can’t think of a saturation of the form because it’s just the inner process that let you there. And when you finish you finish.

— Yes. I’m talking about measuring the body, measuring an object, measuring the time, I mean it was all about measuring for me here. There were two very shy girls, but they were drawing and they didn’t stop. They just kept going and going. From me I just wanted the energy of them, so when there’s 10 people working when I am performing, I am taking them on board.

2 hours 30mins performance

Untitled at Infr’Action Venice 2, Italy (Deframe), 2013. Curator

Jonas Stampe. Photograph by Roland von der Emden

3 hours Performance Untitled at 5th UP-ON Live Art Festival

at Chengdu in China, 2017. Image courtesy of the artist.

— It was so difficult to do because it wasn’t rolling. But that didn’t matter. I was so touched by them. What they have done. This wood carpenter…

— It looks like a monument.

— It was a monument to them. They were so proud of this work. And of course the problem was the responsibility I had to try to achieve a sense of importance to their work. And becomes more than just the action. I think is bigger than just the art, and it motivates me more, and it allows me to push myself. It’s like a win-win situation.

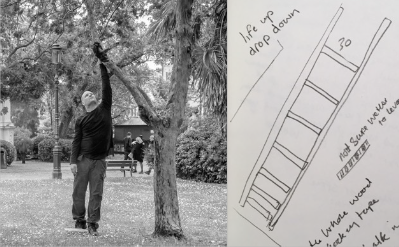

— Achieve. Is this why you draw so many ladders?

— I bet I’ve never used a ladder in the performance,

— So they are just ideas?

— Yes, I have ideas like to make a ladder, I’m quite excited about ladders. Not necessarily to function them as to walk up and down, I like the idea of achievement, climbing up and down. I’ve done a piece where I get on a brick, to get a bit higher. Is called actually “Achievement”. I made one object this year in Venice… during The Biennale. The Venice Biennial. I just wanted to get up a bit higher, as most of the artists this is what I’m trying to do. I personally think is more of an intellectual or a thought thing, instead of a curated thing.

— And what do you think about this relationship between human scale, and monumentality, do you think about that sometimes? I mean when you have a person who is transferring his own movement constantly through the use of some object, in the space, there is a sense of monumentality. Very much thrown to the human scale. Human scale monumentality which is all the time revealing itself. So the way I look at your performances is a bit like this, confronting something intentional because a monument is something intentional where there are memories condensed on it.

— Yes, that’s a nice word. I think performance is kind of like a sense of “permanently-in-the-space”. There is always something left of a performance. Or should be. Just because there isn’t any physicality left… That’s how I approach art, and that is why I stopped making, because actually what was made was the same framework as what was laid. Or the process. I’m not sure that answers your question.

But when I’m doing something, there’s anything that is important. And I left it there. That’s why I’m not interested in the objects. Objects are beautiful. If I would make them as a sculpture, and all the drawings I have them I’m not gonna try to sell them for money. They always put more value in them and they are really not what they were. But with performance, the value is in the work, not in the object. Of course I kept some of these objects.

— These objects – I show you an example, from China, 2012. I have tried to perform until the end and there were these three sticks left. I would love to have one on the wall, because there is so much energy in them. But is nothing like this experience I have, there is nothing compared, even if the object is a piece of stick, even if it was an amazing looking object, it wouldn’t come close to that experience I had. If I would be the public I would take them. An hour on each object swinging… I find it kind of funny. But that is what I want. I want more the idea than the image of it. So I stood there looking at the wall smiling, thinking yeah kind of the same but not quite.

3 hours performance Untitled at Victor-Rousselot Park St- Henri

Montreal in Viva! Art Action festival Montreal Canada,

2015. Photography and film by Christian Bujold

4 hours performance

Untitled in Live Time Gothenburg Sweden, 2016

Photograph by Joakim Stampe

3 hours performance about in New Performance festival

Turku Finland on Saturday. 2017.

Photograph by Julius Töyrylä

[This reminds me of a beautiful lecture I once attended from a university professor in Madrid. She was referring to the experience of minimal art as a type of “nostalgia for corporality”. A kind of paradox lingering on those contained surfaces. And she often described nostalgia as the “territory of childhood.”]

— So for me this experience, I see one of my friend’s kid, swinging a teddy bear, and he was quite enjoying it. I sent it to my friend and said: “look, give it to your son because it was my inspiration”. It wasn’t so much the movement but how he was feeling. I know that feeling, as a kid when you are doing something, and you are just doing it because you feel it makes sense, you enjoy it. It was just that moment, I get that. Not necessarily in art. But like in other kind of situations.

— Do you have any children yourself? Did they inspire any of your works?

— Yes, I have four. And I’m very good at overprotecting them. I made a series of work about overprotected society. It’s based on the witches hat, which we had in England. These spinning playground things which are extremely dangerous. The playground is a protected site, so you see all the kids there, and they were really pleasing them, but they wouldn’t allow them to come close. This work is about how growing is like, and about trying to allow kids to use their own creativity, so they don’t end up being like me.

— This work feels aggressive. Is growing up then a dangerous game?

— I’m not saying I don’t feel aggressive in my performances at all, I feel everything. Anyhow they don’t feel that, the kids. But of course there is that. And this object broke.

— Poetic justice!

— It was reaaaaally disappointing! I never had an object broke, specially because it was scored as 6 hours and there were 3 hours still ahead. Because I put my body weight on this end, so I’m pushing this thing around… but when it completely breaks I just stop, and I look at this person, I can’t do it, and she looked back at me. The meaning, the idea, was perfect. This is duration you know. There’s no rules. If I feel it stops, I won’t carry on. I have too much respect for the time.

— And the numbers in the lowest end?

— I added the object’s weight on my body weight.

— It’s you and it’s the object and the transfer system again. So measuring the body becomes a repeated gesture crossing many of your performances. What else is there?

— I just know everybody there can understand numbers. I’m very interested in this three… I made some artworks about it. All numbers on a black background. That’s my art.

[He laughs]

— So what I did … a year before I was performing in a school with two black objects. This time I asked if I could go to the school and talk to the students and give some lectures. So two days before the New Performance Festival I went to this school. I told them that I was gonna make a boat, and I showed them a picture of the boat. And I explained I would do a performance with it, I would fold it into an origami boat. And I told them I didn’t want to use my numbers, that I didn’t want to do it alone. I showed them this website when I get all these numbers from. Where all meet. Where you can calculate how many people died, and how many people were born. You just take the time a day. It is quite amazing, we are living, and then we are going to die. It’s a great thing. We spend most of our lives not appreciating being born or being alive. That’s probably the most important thing, that’s what I’m aware of most of the time. …. Sometimes you get heavy, but this reality: I’m quite into that.

8 hours performance

Untitled at Spacex Gallery, Exeter, England, 2012

Photograph and video by Patrick Cullum

5 hours performance

Untitled in Beijing Live Beijing China on Sunday, 2016

Photograph by Joakim Stampe

8 hours performance

8 in DigitaLive, curator Jonas Stampe at YouYou Contemporary

Art Centre, Guangzhou, China, 2014

Photograph by Jiayi Chen

— What’s the heaviest weight you’ve ever measured in your work?

— Loss. My mum died in 2012. I had this big show in England. It was really super nice people in this public gallery, and she came and pick the work, it was really great and at the end of it she came and said: “would you like to perform?”, and I was like “great!”. But before the show my mum died (he laughed). It was in the public so it was about education. I was giving workshops, drawing, with kids and students. So I did this performance, with a school table. And I did it for 8 hours. I could do it for 4 hours and then I would move on to this other part of the performance, but then I realized by 6 hours… “well I can do this!”. I opened my arm, and that was very important for me because it allowed me to justify and understand what I’m doing. Is like if you are holding yourself. Yes, that was very difficult.

And since then my work has been different. That loss gave me so much. I feel something was added to me. Just a sense of life, just to justify that you are here this moment, to really embrace it and really do what you want to do.

— Is it from that moment that you become so interested in balancing time? In finding symmetry and working anti-clockwise?

— It’s more the momentum of it. Like in idea meaning knowing. Look at the side, It’s like an 8, but twisted. I’m trying to document how many times I get around. They are numbers. I try to measure the object, but when I start running I’m just running. That’s the momentum! It’s like infinity.

— 8 is their lucky number. Where you aware of it?

— I always do things in China which are more related to China. Two years later I came back. I spend one month before the performance. So I made this video and I just used the outside, the limits of my body to make work. I did two of them, and it becomes an 8, all I see is an 8 because in China is really lucky. And I literally thought: “I need all the luck I can have!”. In this town what they were doing is that they were knocking down lots of building, and there were tons of concrete, dust everywhere. Because it was free, I asked if I could have that rubble and we got them in the space and piled the material in the shape of figure 8, and I walked it in laps for 8 hours durational performance. At the same time, I’m writing in my arm. So now I’m going backward and I’m trying to catch up, I’m trying to balance out the time, which I found really disturbing, and I’m trying to look behind when I’m going backward because I’m trying to look at the past, or touch the past.

It was seven and a half hours before I realized the time runs. And then I had half an hour left. Because of this motion… probably I could say that what happens all the time is that is really hard. My body can’t hold it, is changing, I hope it changes. I always have to rely on the work effect. I always wanted to work very hard to achieve what I wanted. When I went to art school I worked very hard in making objects, but I couldn’t talk about them. And that work effect seemed to have affected me. People really appreciate that. They appreciate I’m working, and they can relate to that. Specially in repetition if they work in jobs that are repetitive, they say “oh I relate to that”.

See more of John Court’s works in:

http://www.johncourtnow.com/

My gratitude to Berlin Sessions Residency and Andrzej Raszyk for the invitation to publish this text.

This e-publication contains a graphic poem in the back cover I realized as a reply gift to John Court,, in exchange for his book . “Portrait of John Court”

© Paz Ponce Pérez-Bustamante

www.pazponce.com pazppb@gmail.com

All the artistic actions by John Court mentioned in this text, claim a freed space in the sphere of language, challenging the rigid limits of the frames of representation restricting the individual to controlled processes of self-editing and self-improvement (institutional, educational, social or behavioral). He calls upon these frames, he even emulates some of its control mechanisms, but he does not subject to its regimes of cultural codification. He re-appropriates difficulty as a territory, a work-in-progress where vital processes resist to become a product themselves, practicing art for its emancipatory potential to project one’s own identity as a form of knowledge and self-development. In a similar fashion to Allan Kaprow’s’ program in “The Education of the Un-Artist”, Court’s works can be approached as open operative models whose functions are understood – and their fruits fully enjoyed, when the beholder stands at the same pre-institutional (and pre-literacy) level, being dedicated to their own lifetime project of knowing, revealed in acts of continuous (self) discovery.

It comes as no surprise he prefers working with children and youth.

Man-in-progress

3 hours with John Court

Paz Ponce Pérez-Bustamante

Berlin, 19th February 2018